Protein Transport Inhibitors : Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Perspectives

Protein transport is a fundamental cellular process that ensures the proper distribution, secretion, and localization of proteins inside and outside the cell. Any disruption of these transport processes whether by natural or synthetic inhibitors has profound implications for biology, pathology and therapeutic development. In this article, we review the mechanistic underpinnings of protein transport, highlight the classes of inhibitors of protein‐transport (especially translocation across the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane), discuss therapeutic and research applications, and reflect on emerging challenges and perspectives.

1. Fundamentals of Protein Transport

1.1 What is Protein Transport ?

In simplest terms, protein transport (Wikipedia) refers to the regulated movement of proteins (or nascent polypeptides) from the site of synthesis to another cellular compartment, organelle, membrane, or the extracellular environment. According to a comprehensive overview, protein transport “is defined as the regulated process by which proteins are moved between cells, often mediated by specific motifs and mechanisms.” ScienceDirecte-an overview

Key sub-processes include:

- Co- and post-translational translocation of nascent chains into the ER lumen or membrane. NCBI

Image from ResearchGate

- Vesicular trafficking from ER → Golgi → plasma membrane or secretory pathway.

Image from ScienceDirecte

- Import/export through nuclear pore complexes (nucleocytoplasmic transport). Nature

Image from ScienceDirecte

- Transport across organelle membranes (mitochondria, peroxisomes, endosomes), though here our focus is on the secretory/translocon pathways. NCBI

Image from ResearchGate

1.2 Why it matters ?

Proper protein transport is essential for :

- Secreted proteins (eg cytokines, hormones), membrane proteins (receptors, channels)

- Maintaining organelle homeostasis (ER, Golgi, lysosome)

- Cellular stress responses (e.g., unfolded protein response when transport fails)

- Pathogen exploitation (viruses hijack host transport machinery)

Disruption of transport can lead to diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, cancer, immunological defects. For example, dysregulation of nuclear transport proteins is linked to cancer and neurodegeneration. Nature

1.3 Major molecular components

Some of the key players :

- The signal recognition particle (SRP) and SRP receptor that target ribosome-nascent chain complexes to the ER.

- The translocon complex (notably the Sec61 complex -Wipedia-) which forms the channel through which nascent polypeptides enter the ER lumen or integrate into the ER membrane. MDPI

Image from ScienceDirecte

- Accessory translocation factors (eg TRAM, TRAP, Sec62/63) for less hydrophobic signal peptides.

Image from ResearchGate

- Vesicle-coat proteins, SNAREs, small GTPases for downstream trafficking (ER → Golgi → plasma membrane).

Image from MDPI

- Nuclear pore complexes, karyopherins (importins/exportins) for nucleocytoplasmic transport.

Image from ResearchGate

2. Inhibitors of Protein Transport

In the context of protein transport, “inhibitors” (Wikipedia) refers to compounds (natural or synthetic) that interfere with one or more steps of the protein transport pathway. These are of interest both as research tools (to probe mechanism) and as therapeutic agents (to block secretion of aberrant proteins, or trap malignant cells). Below we explore the major categories with evidence.

Image from Wikipedia

2.1 Inhibitors of ER Translocation

One of the best‐documented categories is inhibitors of protein translocation across the ER membrane. A detailed review is provided by Kai‑Uwe Kalies & Karin Römisch, “Inhibitors of Protein Translocation Across the ER Membrane”. Pubmed

Key points :

- Translocation into the ER constitutes the first step of the secretory/ membrane protein pathway. PubMed

- These inhibitors may block signal peptide insertion, ribosome–translocon engagement, lumenal folding, or downstream vesicle formation.

- Some inhibitors are broad‐spectrum, others lock in a substrate-specific manner (thus allowing selective blockade).

Major inhibitor examples :

-

Eeyarestatin I (ESI) : interferes with ER-associated degradation and also impairs retrograde and anterograde transport.

-

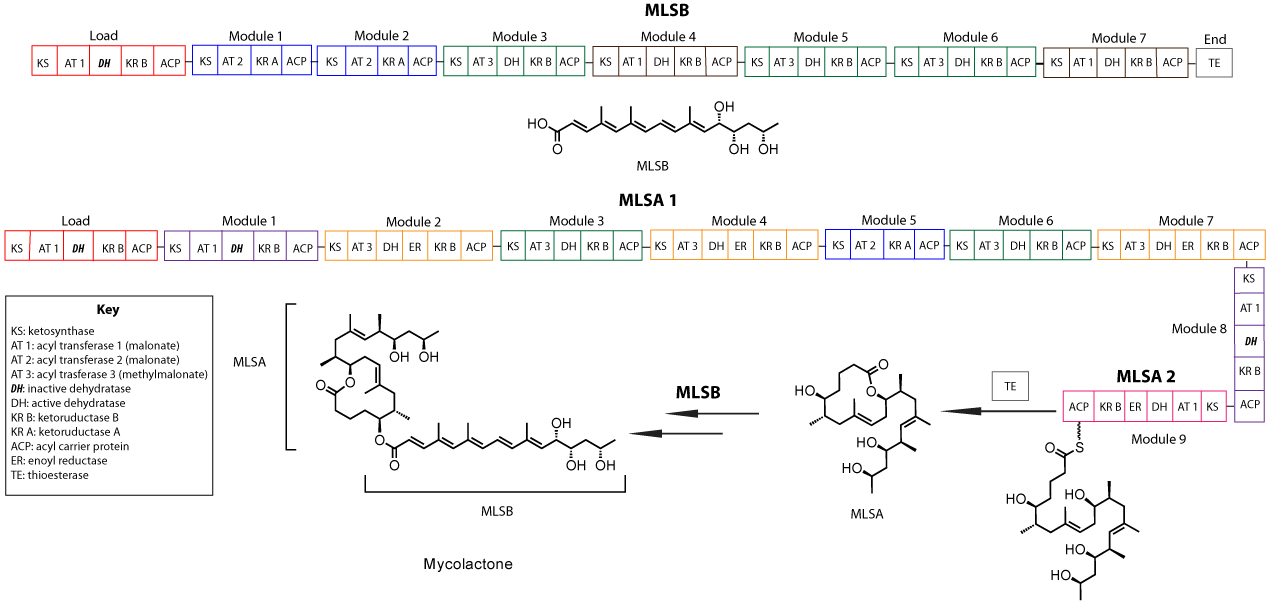

Mycolactone : natural macrolide toxin produced by Mycobacterium ulcerans that non-selectively blocks Sec61-dependent translocation.

-

CAM741, cotransin : cyclic peptides derived from fungal toxin lead structures; selectively inhibit co-translational translocation of certain substrates (eg VCAM-1, P-selectin) by binding or altering Sec61α lateral gate behaviour.

From a mechanistic viewpoint, the process may be hindered at :

- Signal peptide (SP) recognition or binding to SRP.

- Targeting of ribosome‐nascent chain complex to ER membrane via SRP receptor.

- Engagement of RNC with Sec61 and opening of lateral gate.

- Insertion into ER lumen or membrane.

- Lumenal processing (signal peptidase cleavage, glycosylation).

- Folding, quality control and budding into vesicles.

Because transport is so multi-step, inhibitors can act at any of these checkpoints, offering rich mechanistic insight and therapeutic leverage.

2.2 Inhibitors of Vesicular Protein Trafficking

Beyond the translocon, inhibitors of downstream trafficking (ER → Golgi → surface) exist. For example:

- Brefeldin A : a fungal lactone that inhibits transport from ER → Golgi by inhibiting the activation of Arf1 GTPase and COPI coat recruitment, causing Golgi collapse and accumulation of proteins in the ER.

- Other secretion inhibitors that impair vesicle budding, fusion, or cargo sorting (often used in cell-biology assays).

2.3 Inhibitors of Nuclear Export / Import (Transport Across Nuclear Envelope)

While not always classed as “protein transport inhibitors” in the secretory sense, nucleocytoplasmic transport inhibitors are highly relevant. For example, exportin‐1 (XPO1/CRM1) inhibitors (eg selinexor) block nuclear export of tumour suppressors and are in clinical use. The review of nuclear transport proteins describes how dysregulation can be targeted for therapy.

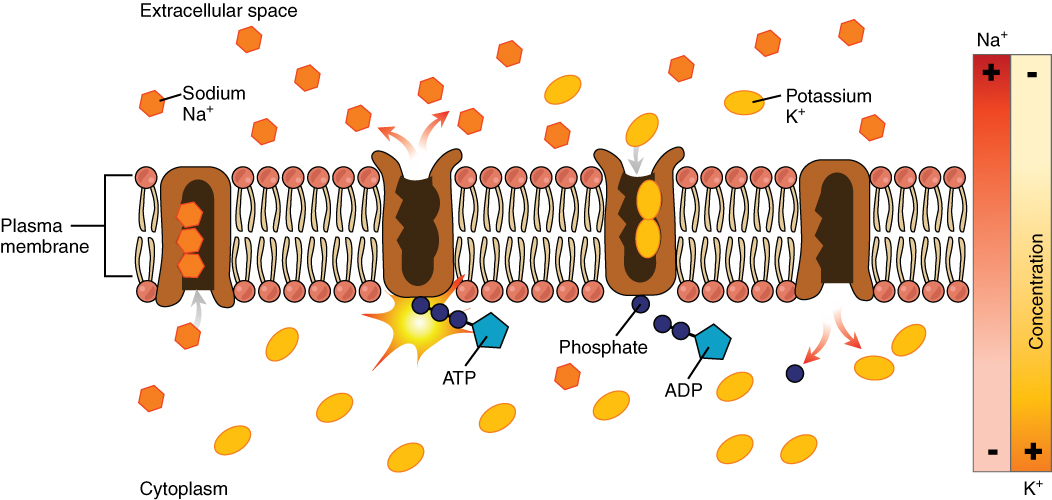

2.4 Transporter Inhibitors (Efflux/Influx Proteins)

Another related class pertains to membrane transporters (solute carriers SLC, ATP binding cassette ABC) that move small molecules (not necessarily full proteins). Although distinct from polypeptide transport, inhibitors of such transporters (e.g., SGLT2 inhibitors, ASBT inhibitors) represent a conceptually related paradigm: blocking transport to therapeutic effect.

3. Mechanistic Insights : How Do Transport Inhibitors Work ?

Here we highlight the major mechanistic features and consider how inhibitors exploit them.

3.1 Sec61 Translocon and its Vulnerabilities

The Sec61 complex is a major gate into the ER for nascent chains. Structural and functional studies show that binding of the ribosome-nascent chain complex induces conformational changes in the lateral gate of Sec61α and displaces a “plug” domain to open the channel.

Inhibitors exploit this :

- Some bind directly to Sec61α (or adjacent subunits) and lock the translocon in a closed or mis-oriented state (eg mycolactone).

- Others modulate the signal peptide–Sec61 lateral gate interface (eg cotransin), interfering with substrate insertion.

- Some block the ribosome-translocon engagement or stall the nascent chain before insertion.

These mechanistic manipulations cause accumulation of proteins in the cytosol or ER lumen, trigger ER stress/unfolded protein response (UPR), and may result in apoptosis or growth arrest, especially in cancer cells reliant on high secretory load.

3.2 Downstream Trafficking Blockade

Inhibition of vesicular trafficking (for example by Brefeldin A) prevents the forward movement of cargo from ER to Golgi, collapsing Golgi structure, altering membrane homeostasis, and causing accumulation of secretory proteins in the ER, thereby triggering cell stress responses.

3.3 Therapeutic Exploitation

Inhibiting protein transport can :

- Block secretion of tumour-promoting factors (cytokines, growth factors).

- Sensitize cancer cells to ER stress or proteotoxic stress.

- Prevent viral replication by denying viruses the host secretory machinery.

- Allow selective blockade of immune-modulatory proteins (via substrate-specific inhibitors).

4. Research and Therapeutic Applications

4.1 Research Tools

Transport inhibitors are indispensable as mechanistic tools :

- To dissect the steps of ER translocation, quality control, vesicle sorting.

- To validate involvement of specific translocon co-factors or chaperones.

- As probes for high‐throughput screening of transport modulators (eg the review of Sec61 inhibitors describes modern screening strategies).

4.2 Therapeutic Potential

- Cancer : Many cancers have elevated secretory requirements (growth factors, extracellular matrix remodellers). Blocking translocation or trafficking can impose proteotoxic stress and trigger apoptosis.

- Infectious disease / virology : Viruses rely on host secretory and translocation machinery to produce envelope glycoproteins. Inhibitors of Sec61 or ER → Golgi transport may offer antiviral strategies.

- Autoimmunity / inflammation : Selective blockade of adhesion molecule or cytokine secretion (via substrate‐specific inhibitors such as cotransin) offers potential to modulate immune responses without global immunosuppression.

4.3 Challenges and Considerations

- Specificity: Many inhibitors act broadly, which may cause toxicity in normal secretory cells.

- Selectivity of substrate: Developing inhibitors that only block one or a few proteins remains difficult.

- Adaptive responses: Cells may up-regulate alternate pathways or stress responses (UPR).

- Delivery, pharmacokinetics and off-target effects remain key hurdles in translational development.

5. Emerging Directions & Future Perspectives

5.1 High-throughput screening and chemical biology

The review of Sec61 inhibitors emphasizes the growth of high‐throughput assays and structural insights to discover next‐generation transport inhibitors. MDPI

5.2 Structural biology of transport machinery

Detailed mechanistic structures (ribosome-Sec61, lateral gate dynamics) are needed to design inhibitors with higher specificity and lower toxicity.

5.3 Substrate-specific inhibition

The holy grail: compounds that block only the translocation of certain proteins (e.g., tumour‐specific secreted factor) leaving general secretion intact. Some cyclic peptides (e.g., CAM741, cotransin) are prototype examples.

5.4 Combination therapies

Since transport inhibition induces ER stress/UPR, there is potential for combination with proteasome inhibitors, autophagy inhibitors or other stress pathway modulators.

5.5 Clinical translation & biomarkers

Identification of biomarkers of sensitivity (e.g., secretory load, ER stress phenotype) will help stratify patients likely to benefit from transport inhibitor therapies.

6. Practical Considerations for Researchers

If you are designing or using protein transport inhibitors in your research pipeline :

- Choose whether you want broad-spectrum or substrate-specific inhibition (depending on your question).

- Validate using orthogonal assays: e.g., accumulation of presecretory proteins, induction of UPR markers (BiP, CHOP).

- Monitor toxicity in high-secretion normal cells (e.g., hepatocytes, plasma cells).

- For translational work: examine the pharmacodynamics, off-target secretory effects, and stress response activation.

- When interpreting data: remember that inhibition of transport often triggers secondary effects (ER stress, autophagy, apoptosis) and these may confound primary mechanistic interpretation.

To synthesise: The inhibition of protein transport, especially at the level of translocation into the ER or trafficking through the secretory pathway — represents a compelling interface of basic cell biology and therapeutic innovation. With increasing structural and mechanistic knowledge of the transport machinery (e.g., Sec61, ribosome–translocon interaction, vesicular coats), we are beginning to see how selective transport inhibitors can be designed. For researchers and therapeutic developers alike, understanding the mechanistic detail of transport inhibition is essential.